Emily Goldsmith: With The New Landscape exhibition, you had some of the brightest, or at least most densely coloured paintings you’d ever done. Then it seemed you almost obliterated that way of working, stripping things down to the point of almost nothing. Now again, with perhaps the most recent works I think you’ve started to come back in a way.

Marc Blake: I had a couple of works in my studio that I hadn’t included in that show and even though I liked aspects of them, I wasn’t really happy with them as a whole. This led to me sanding them back almost entirely as usual, except with these ones, what I started to like was how it looked with parts of the paint completely sanded away and other parts still remaining. I’d done variations of this kind of thing for many years, but never really in this way, or to this extent before. What happened was that the remaining pigment sort of half suggested a landscape and half become just a kind of abstract background in a way.

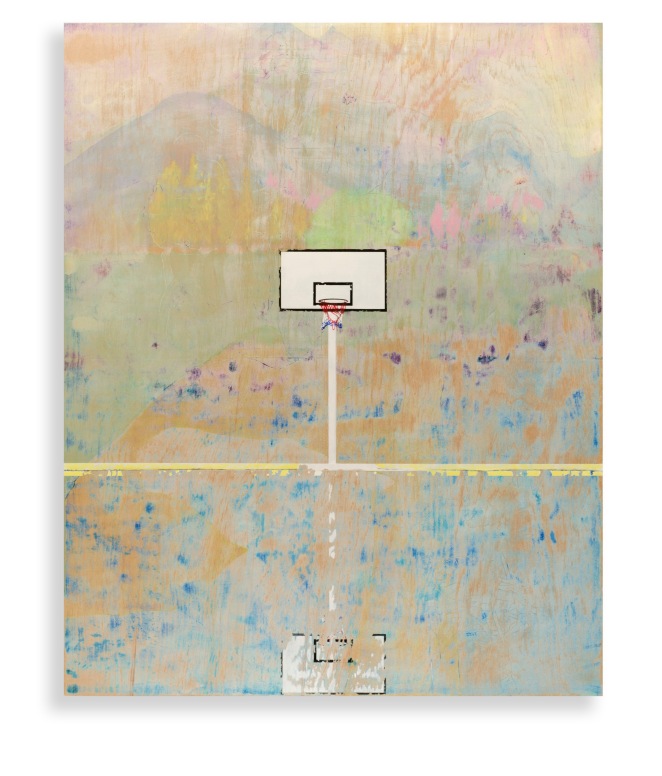

E.G: I think the first one, and I know you’ve talked about his before, was the basketball hoop painting based on the park next to your house.

M.B: Yeah that work was like a kind of accidental revelation, the whole way through making it was like a constant series of accidents that seemed to work together. From how the landscape revealed itself after being sanded back so intensely, to accidentally pasting the image of the basketball hoop on to a photo of the work in progress in Photoshop. It was sort of the peak of making a painting that was very much based on my immediate environment, but it all happened in such a haphazard and free-associative way. In a sense that work was so perfect for me, but at the same time it was a kind of dead end, there was no way I could really reproduce that again.

E.G: In what way specifically?

M.B: I mean every now and again I stumble across an image, like the basketball hoop in the park across the road, that is packed with so much kind of meaning and association, both personally and collectively, that’s like a one-off. The way forward is to either keep using that image for ever, or try and think of another one that has a similar impact, or else change direction entirely. I decided to change direction because the other two ways are dead-ends for me. But rather than completely change, I went back in a way to what I was doing in all the works for that last show and with many other paintings before that over the years.

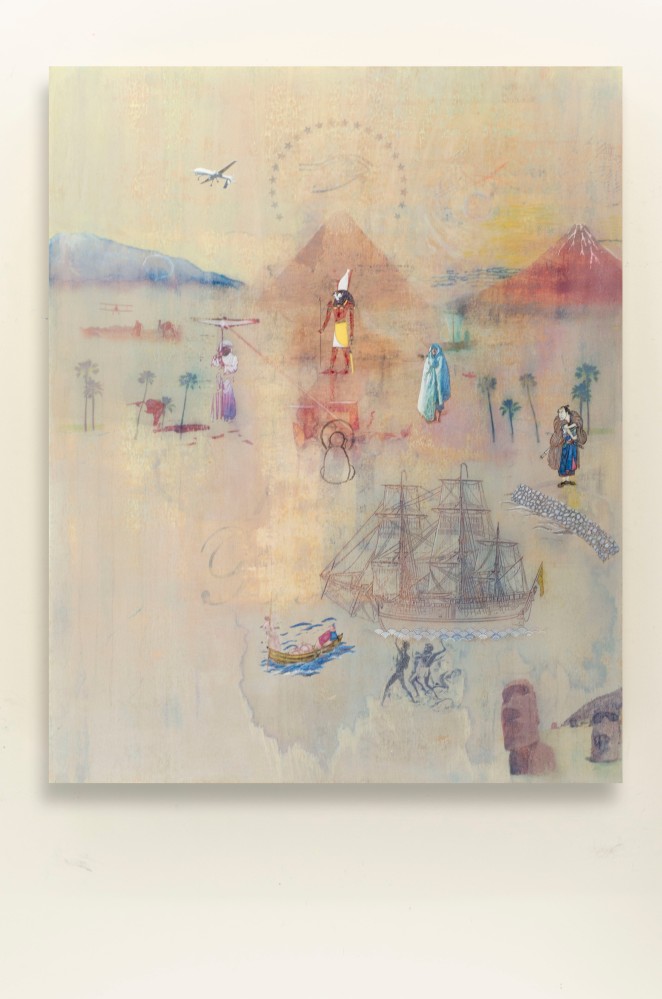

E.G: We have three images I want to ask you about and see what connection there may or may not be towards them. The first is, “Second Sun” from 2015 and then “Pacific” and the newest one you’re still working on at the moment.

E.G: With “Second Sun”, there are several figures and trees and few other things that are fused into the paint in a kind of swirling, neon dreamscape. There’s no clear realistic intent with the work, it appears almost completely abstract from a distance and the pigment is intense and sitting on the surface of the board.

M.B: Yeah like we’ve talked about before, pouring all those very thin layers of colour on at the start of the work enabled me to give up so much control. I had no real idea how it was going to end up when it dried. Even though I could manipulate it a little along the way, it was more of less just down to wind and sun and gravity. Once the layers dried, I could then start to imagine a kind of landscape and gradually, one by one, figures or whatever would start to suggest themselves and I’d look for pre-existing images from any source to try and best convey those ideas.

E.G: You’ve always used pre-existing images.

M.B: Almost exclusively in everything since about 2008. That doesn’t mean to say the painted image necessarily comes out looking anything like the original source – sometimes it does, usually it’s completely different. The only thing I care about is that a pre-existing image served as the starting point. Photos, things from other paintings, graphics, drawing, trawling the internet, whatever. Ultimately it’s all the same to me. A way to take something that already exists in the world and bring it directly into the context of the work.

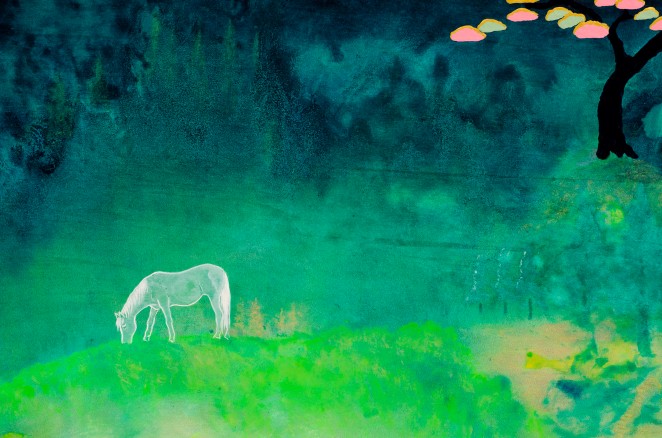

E.G: With “Pacific”, the intense pigment as well as the imagery has been almost completely removed or obscured, almost gesturally, or violently.

M.B: The first painting on this board was very bright, with deep maroons and golds and it was all quite thick. Then that got mostly sanded off and another painting went on there and then that got mostly sanded off and on and on for about five or six utterly different works over a series of months. Yet at each stage of sanding, something of those works remained and added to what was already there. The more I worked, the more it started to suggest something to me, a kind of Pacific scene impacted by conflict.

E.G: You’ve also developed a new way of incorporating images it seems.

M.B: Yes for the past three or four paintings I’ve been working on a new way to get images into the work, rather than tracing the outlines of prints into the board. Essentially it’s like what I’ve alway done, just in a different way. The difference is that now images kind of sit on the surface as well as soaking into it at the same time. In “Pacific”, this is probably the first painting I’ve ever done where all the imagery is really “behind” the background colour and the board itself seems to almost float out in front. I’m not even sure that’s physically possible.

E.G: Defying physics!

M.B: Definitely defying the traditional logic of figure and ground anyway.

E.G: “Pacific” is another very abstract work at first glance. There is no obvious imagery until you look closer. Much in the same was as ‘Second Sun”.

M.B: Yeah this work actually had so many images along the way and all of them were quite graphic and obvious, but for whatever reason I’d just keen sanding them back. The result is that the sanding started to become the work and ultimately it reached a point where I was looking at it and it just seemed finished. Kind of scarred. Lately I’ve been really interested in old Asian paintings on stone and paper that have deteriorated, or been damaged, or defaced, or altered over centuries. There is a real feeling of time in these latest paintings and I think without it they wouldn’t really work.

E.G: Despite the fact that for almost everyone else, this work probably seems completely unfinished or like a mistake even.

M.B: Right! It’s all quite funny. It probably looks like the least realised work I’ve ever done, but it’s almost completely the opposite.

E.G: However obscured or faint though, there are still images in the work.

M.B: So many times lately I’ve sanded these colourful paintings away and thought that they could be finished just like that. They’re actually quite beautiful objects in their own right. It really made me question about why I feel compelled to add images at all. Ultimately it comes down to what kind of painter I am and that is someone who thinks in terms of images. A painter who wants to have an image, somewhere, somehow in the work. It doesn’t always matter to me how clear or obvious they are. If I was a different kind of painter I could probably just leave them as purely abstract works. Who knows, maybe I will at some point, but what’s important to me is that everything is constantly changing and progressing in terms of the work itself, in terms of the working. Not just me making some kind of radical strategy for some external reason.

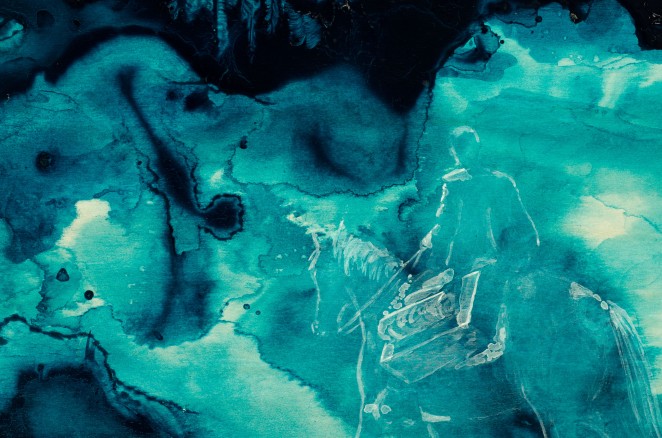

E.G: Finally we have a work you’re still making, which from what you’ve just been talking about may be totally gone or different tomorrow, but I’ve seen this progressing piece by piece in detail photos on Instagram and it’s crazy how many twists and turns it’s taken.

M.B: And that’s only the photos I’ve posted, there’s been so much more than that. I can’t even remember what this work was before, but it’s had so much sanding and layering of things that it’s reached a new point. A huge amount of detail and sources.

E.G: The background itself is stripped back and muted, it’s almost featureless, yet somehow you’ve still managed to make a landscape out of it.

M.B: A landscape is really an image made of other smaller images. What people tend to forget is that there is really no such thing as landscape. There’s always only just a truly massive amount of minute information, which our eyes tend to combine into a larger, simpler image to enable us to process it. A perfect example is when I look at these huge mountains behind our house. Usually we just see what we call a “mountain”, this enormous jagged thing. It almost looks flat. Really though it’s billions of rocks and stones and pebbles and dirt, all just lumped in the same place. The closer we get, the more detail we tend to make out, but it isn’t until our face is literally right in the dirt that we really start to see what the mountain physically is. Sometimes when the light is right, from a distance I can start to almost zoom in on details on the mountains and then again further in on details within that and it’s mind boggling. If our eyes suddenly worked differently and we saw all of these nearly infinite details rather than the “mountain”, I think we’d go insane. But in a way this is really so much closer to how the universe is. An infinite amount of detail. Depending on your position to something, it takes on a whole new form. For that reason I try to make paintings that are as subjective as I can, in every possible way. As you move closer or further away the story changes, the relationships between figures and objects change, the patterns change, the images change, the techniques change, the whole work changes. That’s what I look for in painting.